About WaveFront, Inc.

Based in Chatham County, N.C., WaveFront, also known as WaveFront Marine, is a family-owned-and-operated sailboat accessory business. The company manufactures and sells two models of its advanced tiller-steering product, the TillerClutch™ . It also sells associated accessories and seven types of handcrafted tillers. All products are available through the Shop page and through retailers in the United States and in Australia, Canada, France, Japan and the UK. To obtain more information, please send us a message on the Contact page.

About Pete & Katherine

How They Started WaveFront

In 2006, native North Carolinians Pete Crawford and wife Katherine Smart founded WaveFront Marine in Chatham County, NC. Their dream was to develop innovative sailing products to help people across the world enjoy, understand and have better access to the marvelous world of sailing.

The company’s first product, the TillerClutch, was designed and patented by Pete, an avid sailor, civil engineer and inventor. Katherine, who has an extensive background in marketing and communications, developed the company’s brand and then launched the TillerClutch with Pete at the Annapolis Boat Show in 2010. Today, the TillerClutch is sailing around the world, fulfilling the company’s mission to answer unsolved sailing needs with novel products that are safe, reliable, durable, effective and easy to use.

The Evolution of the TillerClutchTM by Inventor Pete Crawford

I am an engineer and inventor who has sailed both single-handed and with crew for many years. My need for an effective mechanical tiller-control device really hit home in 2004, when I sailed my San Juan 21 to Cape Lookout, North Carolina in conditions rough enough to warrant taking the not-so sheltered route through Back Sound, foregoing the more favorable ocean route. Many sail changes kept me busy as the wind frequently changed. I was navigating are shoal waters, and several groundings required me to dive below to adjust the boat’s deep swing keel. Needless to say, these were precarious operations for me without crew and on so tender a boat.

My search begins

Though I managed to arrive in one piece, I sorely wished for a reliable and instant way to secure and adjust the helm. Upon my return, I carefully listed my requirements for such a mechanical device. Armed with my list, I searched catalogs and the Internet, confident that someone had surely solved this age-old problem to my liking. I was looking for a device that would:

- Engage/disengage the helm instantly, and provide for quick steering adjustments

- Hold the tiller firmly without slipping in reasonably rough conditions

- Not break under heavy use

- Release completely for free steering with no drag when disengaged

- Not rely on constant friction that you must overcome to steer

- Retain the optimum grip setting when released and reengaged

- Be a refined piece of sailboat hardware

- Have a compact design, not much wider than the typical tiller

- Not snag the main sheet when jibing

- Resist corrosion without relying on plastic construction

- Have fully rounded edges and not pinch you (sailors get enough nicks and bumps as it is)

This was a tough order to fill, but I wasn’t willing to stop looking until I had found a product that could meet all of these requirements.

My needs were unmet

I found nothing on the market that came close to what I wanted. One popular product operates on the assumption that friction applied to the helm will ease the effort of steering. Although it is a good idea, this principle holds true only for light-wind sailing. Overall, I found some neat gadgets as well as some partial solutions, but nothing that met my demands as a single-hander. I then tried the many homemade rigs and rope tricks that others have used. There were some clever ideas, but each was too slow to adjust, wouldn’t stay put, jammed in critical moments, or wouldn’t allow for an “emergency override.”

Necessity is the mother of …

Finally I thought, “Why not finish the job and address all the issues with a new solution?” Optimistically, I set to work to develop a tiller controller that would satisfy my long list of demands. I put in long hours in the workshop doing computer design, engineering calculations, load testing, strength testing, and machining out parts for prototypes.

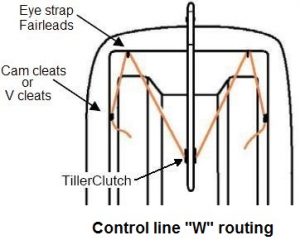

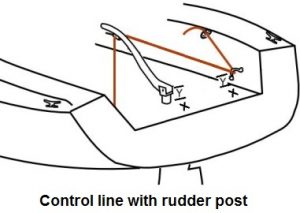

It quickly became apparent to me that a tiller-mounted device that engages a control line routed back to the transom was the safest, most effective way to go. At first, a miniature winch drum with a clutch mechanism sounded good, but problems with practicality led me to consider an arrangement using pulleys and a jamming wedge. I reasoned that if a rope can easily jam in a block by accident, surely it could be done intentionally. However, this too proved problematic. Eventually, I resolved that the best solution lay in developing a specialized rope clutch.

Trial and error ensued

Over the months, I built, refined and installed a number of prototypes on different boats. With the help of friends and family, I conducted sea trials and measured forces in various conditions (a great excuse to go sailing!). We varied our test sails across many North Carolina waters, both fresh and coastal, in addition to the Chesapeake Bay. Sometimes these tests resulted in improvements to my design, while others caused me to entirely scrap a design and return the drawing board once again.

Each refinement or new design seemed to require more math and precision as the tolerances and detail of the parts increased. I eventually began to do all my design work on computer with a sophisticated CAD program, and I wore out my calculator crunching numbers and formulas. I realized that I needed to upgrade the equipment in the workshop to machine the detail and tolerances I needed. So, I raised the money and invested in a combination milling and lathe machine, and the work and testing continued.

Another requirement emerges

At one point, during an ocean trial, I watched as another boat broke a sound rudder under heavy wave action to the beam while the wheel was lashed down. So there needed to be a definite limit to the holding power that the device is allowed to apply to the helm. This decision added one more requirement to my already long list:

12. Have a defined slip factor to protect rudder and allow the helmsman to overpower it

During later tests, especially on larger boats, I was surprised to learn that the sailors were applying my prototypes often, even when plenty of crew was available. When the wind was fair, and the chop was easy, we would trim the sails close-hauled and just lock the helm. Several different size boats were sailing on very long tacks with little or no steering correction. Even after self-rounding up in the big puffs, some boats would resume course as well as, or better than, the helmsman would have done.

Another surprise was the use of a tiller pilot on a larger test boat. These little steering robots are great friends on long, multi-day voyages, but they can be a bit noisy, drain the batteries, and often take precious time to engage and adjust to a particular course. Although the prototype and tiller pilot could not be engaged simultaneously, many times we found ourselves quickly disengaging the tiller pilot and engaging the prototype to deal with a bend in a channel, dodge a power boat, or respond to a wind shift.

Throughout the development process, my basic design concept evolved, sometimes changing radically (and painfully). For a long time, each version was an improvement, but fell short of my requirements or resulted in a device too complex to manufacture. Eventually, I learned that the design must evolve from one requiring many interworking parts to one with few multifunctional parts. This change in design concept simultaneously improved cost effectiveness and reliability for harsh marine conditions.

Discovers the best design

Eventually, with yet another complete redesign, I knew I was onto something that our company, WaveFront, Inc. could produce and stand behind. Several refinements and much testing later, the TillerClutch was borne.

We wanted to ensure that each product sold would work as well as our final prototype. Because every part except the mounting screws must be custom-made with a high degree of precision, WaveFront employs machine shops with advanced equipment and technologies to produce parts to exacting standards. In house, we do the final processing of parts, assembly and multiple testing to ensure proper operation and durability.

I am glad to find that I now long to repeat my San Juan 21 trip to Cape Lookout with the help of the TillerClutch. What a difference!

Pete Crawford

Founder, WaveFront, Inc.